The Stranger from Hohenwald, Tennessee

William Gay's "I Hate to See That Evening Sun Go Down"

William Elbert Gay was born in the small town of Hohenwald, Tennessee, in 1941. He served in the Vietnam War. He painted houses and hung drywall. He was a carpenter. When he was a boy, he fell in love with Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel and decided he wanted to be a writer. In the 1970s, he corresponded briefly with Cormac McCarthy, one of his heroes, and Cormac mailed him back some notes on whatever Gay’d been working on. William Gay didn’t publish a story in a literary journal until 1998. He was fifty-seven years old.

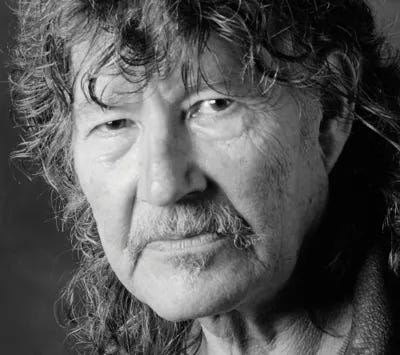

I met William Gay in 2009. I was a student at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, and William was the visiting writer at the college’s writer’s conference. Undergrads submitted stories for a workshop held by this ragged scribe from Hohenwald, a town I’d never even heard of in which there is, I’ve heard, a very robust elephant sanctuary. When I went up to the conference hall in the UC, I saw Gay standing around under bright florescent bulbs in lightwashed jeans and dirty white sneakers and a blue blazer rumpled over a Bob Dylan tee shirt. He had a gray ‘stache and a curly mullet that looked like it’d been dipped in a pot of peanut oil. He looked about a hundred and thirty years old.

In workshop, he told the group about corresponding with Cormac in the ‘70s. He’d get notes back from Cormac saying things like, “You talk about the moon too much. Why so much moon? Less moon.”

William got to my story in the rotation and commented on how it felt more like a “mood piece” than a story. Basically his critique was that nothing really happened in it. I think I’d read a lot of stories like Hemingway’s iceberg-quintessent “Hills Like White Elephants,” but I’d also read stories like Gay’s “Bonedaddy, Quincy Nell, and the Fifteen Thousand BTU Electric Chair” — you can imagine that some shit might go down in a story that’s called that — and I didn’t yet know how to reconcile the two. At that point, I was simply wading the waters of language. Attempting to craft a narrative with movement and drama and danger hadn’t yet clicked for me, far from it.

But a buddy and I smoked cigarettes with William after the workshop, and I brought up how I was also a fan of Cormac McCarthy, had loved All the Pretty Horses. Gay said, “Yeah, I wasn’t as big on that one. I tend to like his old stuff a lot better. The darker Tennessee stuff he was doing in the seventies.”

I took away two big things from Gay that day: Cormac McCarthy’s Tennessee gothic novels of the ‘60s and ‘70s are his best work, and that, in a story, something should probably happen. I wound up driving him in my Jeep to the theater across the Tennessee River where he’d be reading from his novel Twilight, and that was the third big thing I got out of it. William Gay died three years later.

William Gay was a country maverick writer’s writer with no existing writerly credentials like an MFA or any glossy bylines before landing a story in The Georgia Review and getting an agent and publishing The Long Home, his debut novel, in the late nineties.

In that regard (a Tennessean, no MFA, no journalism on the side), Gay wasn’t unlike his hero McCarthy, but some readers make too much of the comparison. I’d say he’s receded somewhat from literary chatter because he’s seen as a sort of Cormac Lite (Gay didn’t do himself any favors by likewise omitting quotation marks from dialogue). Gay’s prose lies somewhere between McCarthy’s sparer (Child of God) and more maximalist (Suttree) registers, crafting his own imagistic gothic timbre, laced with a ruminative lilt wrought by his very genuine working class cred, and a childlike wonder in his descriptions of the natural world less harsh than McCarthy’s.

A mouthful way of saying: Gay found a voice uniquely his own. Makes sense he used McCarthy’s Tennessee era as a guidebook. Aside from early Cormac, there wasn’t much else from which a gothically-minded rural Tennessean could draw inspiration.

Gay’s fiction is devoutly Tennessean and devoutly, eerily bucolic. Naturally he picked up where McCarthy left off, and took hell’s own amount of time to develop a mastery of scene-setting and sentence-craft without neutering his decidedly ornate aesthetic.

Here’s the opening scene from William’s story “A Death In the Woods”:

Carlene was standing naked before the window when Pettijohn awoke. She was holding the curtains aside with an upraised arm and she was peering into the night, the flesh of her left breast lacquered by a pulsing light that cycled red to blue, red to blue, and back again.

What the hell is that? Pettijohn asked.

I don’t know, she said. Lights.

When she turned from the window, her eyes were just dark slots in the shadows of her face and lit so by the strobic light she might have been some erotic neon succubus he’d conjured from a fever dream.

Gay breaks a “rule” (opening with the protagonist, Pettijohn, waking up), and then wastes no time telling us something’s going down, without explicitly telling us: Carlene’s breast pulsing red to blue and red to blue. Police cruiser lights. He establishes their relationship — Pettijohn’s distrust of Carlene — via Pettijohn’s POV in close third, his perception of Carlene as a neon fever dream-succubus, with an odd and oddly passive syntax in that last paragraph, one that achieves an organic rhythm, and is stacked with detail and evocative diction — dark slots, strobing lights, neon, succubus, fever dream — yet transmits a singular, clear, almost cinematic image.

A scene in which a couple is in their bedroom, at night, could be the setup for some tedious domestic realism story whittled down by over-workshopping, but Gay’s setup here is hundred-proof-potent and lurid and ready for danger.

A hell of a novelist (his best might be Provinces of Night), Gay’s finest work is the story collection I Hate to See That Evening Sun Go Down, a book that ought to be on every short story-lover’s shelf, warped and tattered by repeated use. The compactness of the short form allowed Gay to keep a steadier hand at the wheel, by which his aesthetic vision reads as more fully his own. The collection is a master class for anybody who values a balance between tired-but-sometimes-reliable MFA craft platitudes and an unflappable artistic vision; as in the collection’s title story, exquisitely structured narratives are heightened by poetic prose and hilarious calamity, violence, and death, as well as Gay’s love of the natural world — and of music.

The needle hissed on the record and there was Rodgers’ distinctive guitar lick then a dead voice out of a dead time still holding the same smoky sardonic lilt: She’s long, she’s tall, she’s six feet from the ground.

The old man was lost in the song and didn’t hear the girl until she was in the room. He turned and she was crossing the threshold. She had a plate in one hand and a tumbler of iced tea in the other. Jimmie Rodgers was singing: I hate to see that evenin sun go down, cause it makes me think I’m on my last go-round.

He arose and lifted the tonearm off the record.

Gay allows his stories to breathe, build an atmosphere. Gay was a tonal sorcerer. It is very important, Gay shows us, to suffuse story with, for lack of a better way of putting it, a fucking vibe.

At first light he was up as was his custom and in the dewy coolness he went up the slope behind the tenant house following the meandering line of an old rail fence he himself had built long ago. At the summit he paused to catch his breath and stood leaning on his walking stick peering back the way he’d come. The slope tended away in a stony tapestry and the valley lay spread out below him in a dreamy pastoral haze and mist rose out of the distant hollows blue as smoke. The sky was marvelously clear and on this July morning each sound seemed distinct and equidistant: he could hear cowbells on the other side of the woods, a truck laboring up a hill on some distant road. These sounds and sights reminded him of his childhood long ago in Alabama, and they caused a singing in his blood and a rise in his spirits, he could hear his heart hammering strong and fierce as when he was a boy. He was alive and the world alive with him and he had come back to it without either of them being changed.

I could maybe spend an hour-long class dissecting all the ways in which this paragraph is a lyric, tonal and visual marvel. It seems almost like something an editor would want to cut so as to keep things moving along but William Gay evidently got lucky with his editor, somebody who knows that fiction is not to be reduced to a form less accommodating to human feeling, interiority and our our experiences of place and the natural world than film. If Terrence Malick can do it on the screen, the skilled writer ought to try it out on the page.

Gay allows his characters to wander and think and observe, but he also knew, as he’d taught me, that shit still needs to happen, and he wisely situates such gorgeous passages before, after, and in the midst of pulsing scenes of great conflict, suspense, and fire. And Gay tends to set us up with a pretty severe conflict from page one. In this story, well, there’s no need for explaining it. Here’s the opening line: “When the taxicab let old man Meecham out in the dusty roadbed by his mailbox the first thing he noticed was that someone was living in his house.” The reader knows there’s trouble afoot right from the get-go and by the time we get to that whimsical passage above we already know there’s going to be enough of a payoff that we don’t mind walking around the pastureland with Meecham for a little while, we might even pause with the old man while he spins one of his Jimmie Rodgers records.

And we do. We know there’s danger just around the corner. Might as well take a breath and soak up some scenery before shit hits the fan. Gay delivered the best of both worlds — poetics and narrative horsepower — in ways most writers just absolutely cannot do.

In one of the collection’s masterpieces, “The Paperhanger,” our narrator opens with this: “The vanishing of the doctor’s wife’s child in broad daylight was an event so cataclysmic that it forever divided time into the then and the now, the before and the after.”

I’m not necessarily keen on the maxim that a story ought to start with a conflict right away, the “dead body on the first page” philosophy. This notion seemed to take hold in the late aughts and 2010s (based solely off my own observations submitting stories to high-end literary journals at the time and getting a sense of what editors were looking for): we need conflict right away, or, the oft-repeated we need to know what our character wants. Many, many great stories have been rejected from literary journals because the first few lines weren’t hooky enough. The bottomless riches of longform prose ought to render fiction an incredibly malleable art form and therefore “hook the reader” dogma is more than a little absurd, however, it does serve its practical purposes — and obviously helps grow an audience. But I don’t think William Gay followed any “rules” beyond his own wild talent and instincts toward good old fashioned storytelling.

With Gay we get everything. Drama, suspense, readability and extraordinary lyricism. It’s why his main man Cormac was so successful. Crime writer James Lee Burke also works in this register. It’s poetry you can grab a bag of popcorn for.

Aspiring prose stylists who’d also like to learn how to write a gripping story should order a copy of I Hate to See That Evening Sun Go Down right away, but so should everyone else. This book is part of the pantheon of essential Southern Gothic story collections, with books like Airships and A Good Man Is Hard to Find.

The bulk of Gay’s work was published in the twenty-first century, a time in which I think there’s been a little bit of a drought of Southern Gothic fiction in which there’s real magic to the writing, not just grit lit and fast-paced-crime-plus-psychopreacher (which I have no problem with).

As folks incessantly decry a lack of strong literary fiction in our era, the term literary fiction has become increasingly vague — and that’s because it is. The dense thinky novel of olde, of social pontificate-iness and philosophical digressions might be an endangered species simply because we have too much information at our fingertips now anyway. But for my money a work of “literary fiction” is any narrative in any genre that exercises extreme care at the sentence-level, to the extent that big emotions can emerge in the reader by a single turn of phrase. And it never hurts to give readers a good story. A story about human beings in trouble by which to anchor this language. Gay gives us a pretty reliable guidebook on what good literary fiction looks like in the twenty-first century. All hail the lyrical page-turner.

Thanks for this. This prompts me to read deeper into Gay, have only read a couple of short stories. He reminds me a lot of Harry Crews, a master of Southern Gothic, whose short story class I took at the University of Florida. There were 18 classes and Crews showed up drunk for half of them. The other half he didn’t show up at all and his teaching assistant had to stand in. Still, it was a great class. This also prompts me to go back and re-read more early McCarthy and the Tennessee books, although I’m gonna have to steel myself for another visit to Child of God. Mighty dark stuff. I look forward to reading more of your posts.

Wow what a neat dissection. I’ll be on the lookout for sure. You had me at “He served in the Vietnam war.” I’ve worked side by side in heavy construction with quite a few VVs and there’s a lot going on in those heads. Thanks for the intro.