Slasherland — Three 6 Mafia's Southern Gothic

Jordan's Dream - Rhymes for Satan - The Wretched 2000s - Xanax Grimscape - Dawn of the Living Rage - Escape Into the Neon Smoke - Nickelback Country - Rubber Band Dance - and more!

Memphis is an evil place. Throughout my childhood, it was overrun with crime and mayhem. People walked around like zombies high on drugs. I felt like Memphis actually was hell.

- Juicy J, Chronicles of the Juice Man: A Memoir

JORDAN HOUSTON THE THIRD might’ve been in some bedroom he shared with his brother Patrick — “Project Pat” — reading Soulsville, U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records, a book he’d read about a hundred times, when his grandmother shouted for the boys to “Get down.” Gunshots cracking outside the apartment.

These were regular occurrences in Houston’s neighborhood in northern Memphis, Tennessee, in the 1980s. It was a slums cordoned off from the city’s white neighborhoods, a sweltering mid-South war zone, its incredible violence ignored by the Memphis police. If the cops showed any interest in its people, it was only to catch them on the right side of the tracks and beat their asses.

Houston’s father was a preacher hollering the good word, his mother a substitute teacher and librarian. No cursing in the apartment. But in the area, needles were strewn all over the streets, and the cult leader Lindberg Sanders (who’d called himself “Black Jesus”) had awaited The Moon Event and its resulting massacre — vestiges of the Voodoo Village, which Houston’s mother beheld as a child, a neighborhood in which homes were adorned with crosses and stars and dolls.

In Houston’s mid-eighties North Memphis, hustlers roamed the cracked sidewalks wielding rusty pistols, pushing rocks to ravenous hordes of the harried undead.

Jordan dreamed of musical stardom. He wanted to be great. He listened to the Stax legends, he listened to hip-hop. Run-DMC and Whodini. He listened to Michael Jackson and George Michael and Elton John and Pat Benatar and Prince. He cobbled together a four track recorder from shit he’d found on the street. His parents were skeptical. Horror all around him, he sought solace in the slashers and monster movies of the time. American Werewolf In London was a particular favorite.

In the southside of Memphis, a more affluent community, Paul Beauregard had painted Chucky from Child’s Play on the back of his car. When Houston first met him, Paul was walking around with a Chucky doll.

Both aspiring DJs in the early 1990s, Paul and Jordan would later form the Backyard Posse with Paul’s nephew Ricky Dunigan, known later as Lord Infamous, or, “The Scarecrow,” a fellow acolyte of the macabre.

Together they’d forge an expression of Memphian horror more sinister than the realist gangsta rap pouring out of LA and NYC. A new mode of rendering the dangers of oppressed and impoverished and criminalized communities, embracing and subverting the Satanic Panic of the era.

When Gangsta Boo, Crunchy Black and Koopsta Knicca joined the crew, Triple Six Mafia was born. Then they renamed themselves: Three 6 Mafia. Local radio refused to play their songs, and Three 6 came off a little less 666 than Triple Six. Jordan Houston — now “Juicy J” — figured Three 6 just sounded more like some random-ass numbers and maybe they’d fool the disc jockeys. It worked.

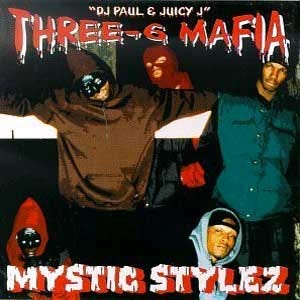

In 1995, Three 6 released their full-length debut, Mystic Stylez, an eerily lo-fi blend of gangsta rap, early iterations of crunk and trap music, and a sonic landscape inspired by horror film scores, its menace and mystery heightened by grimy production, homespun beats, and a taste for the grotesque. Underground shit, informed by an ‘80s upbringing, amid a culture allowing grindhouse aesthetics into the mainstream — slasher flicks and Mad Max and Conan the Barbarian and Re-Animator and Killer Klowns from Outer Space — a moviehouse, VHS-and-late-night-TV bloodbath flooding American living rooms, smoked-out basement dens. Jason. Freddy. Michael Meyers. Kiefer Sutherland in fangs, eyeliner and a platinum mullet. The vampiric punktry bumpkins of Katheryn Bigelow’s Near Dark. Houston and Beauregard and the rest of the Triple Six crew escaped the horror of reality and into the caped, cathartic maw of eighties schlock and terror, into the shadowed, crimson-cartooned recesses of slasherland.

I, and many others like us, have sought solace from hopelessness in the works of John Carpenter, Dario Argento, Wes Craven and Tobe Hopper. Now, folks like Jordan Peele, Coralie Fargeat, Ari Aster, Robert Eggers, Ty West and Panos Cosmatos have helped shepherd a new horror renaissance for the disaffected amid a morphed era of algorithmic dehumanization, intellectual dilution, a now-more-visibly depreciated middle class and the cultural stranglehold of a confusingly bizarre partisan politics. Triple Six felt the power of the macabre in their early work, and knew that a hunger for devilment, even as a surface-level gimmick, could help a body transcend the terror. They forged a youthful, underground style of rap that captured the darkness. Mystic Stylez is its purest expression.

In “Break Da Law ‘95,” ominous, distorted synths and shrieking phantom sirens and John Carpenter, Halloween-style piano loops swarm about a posse chanting break the law break the law break the law break the law as though in a trance of criminal-mindedness and murder, DJ Paul beckoning his listeners, his victims, “Come with me to Hell.”

Bell-toned, evil dollhouse synths trill in the background while Jordan “Juicy J” Houston, on the album’s title track, raps: “Deep when we creep, take your last breath. Roll up a tombstone, smoke a blunt of death.”

In “Now I’m Hi, Pt 3,” a deep, heartbeat bass pumps while a breathy choir — Brian Eno’s Music for Airports, “2/1”, but in a DOOM level — glissades evilly in back of dreamscape chimes and another chant-style intro. These chants are a precursor to the 2000s Crunk Boom, as were the Mafia’s nihilistic and almost appalling appeals to getting really, really fucked up all the time.

The four horsemen of the Mafia’s subject matter: Satanism/the macabre, violent criminal acts, fucking, and getting fucked up. These would remain tenets throughout their career, even as the devil thing diminished with each new LP.

By the time Most Known Unknown came out in ‘06, their first significant commercial success, Three 6 Mafia had devolved fully into party rap. Most Known wasn’t a bad crunk record (and they’d had every right, they more or less invented the genre), but what they’d been doing in the ‘90s and early aughts was a unique, hip-hop expression of the Southern Gothic tradition, with its emphasis on the region’s darkness and decay and monsterdom.

Three 6 had, essentially, inverted the hugely mainstream gangsta rap of the early 1990s into a horror movie vision of the poverty, gang violence and drug-induced squalor they’d grown up around. While LA and NYC titans like Dre and Tupac documented their milieu with an approachable realism and clarity and silky, funk- and soul-inspired beats, Triple Six conjured real monsters, and played their roles accordingly, Lord Infamous, “The Scarecrow,” caroling, “Mystic Stylez of the ancient mutilations, torture chambers filled with corpses in my basement. Feel the wrath of the fucking devilition. Three six mafia, creation of Satan.”

I was eleven or twelve, in the fifth or sixth grade — it was 1999 or 2000 — sitting next to my buddy on a charter bus heading for a school field trip to Gatlinburg, Tennessee, when he opened his giant CD case.

Gatlinburg is a gaudy tourist town at the edge of the Great Smoky Mountains. Our class had gone on a two night trip, the purpose of which escapes me. I remember us hitting up the arcades, laser tag emporiums, and a Ripley’s Believe It Or Not haunted house off the main drag (It was terrifying, I still think about it). We went to Dollywood, a Dolly Parton-themed amusement park (if you don’t already know).

I’m sure we’d visited Cade’s Cove, a historic preserve of Appalachian Frontier cabins and chapels. I’m sure the whole thing had some kind of educational lean. This was a liberal arts magnet school, though, and we had us some fun. We all stayed in a hotel and I got to share a room with a bunch of my pals and we’d talk about girls and listen to music. We roamed the hotel with lax supervision. I had a girlfriend, and I bought her a sea turtle necklace at some gift shop, but I was too nervous to sit next to her at dinner that night at the Golden Corral buffet — it was all girls at her table, all boys at mine. Her friends called out to me, laughing, because the sea turtle was missing a leg. I didn’t know it was like that when I bought it. I was extremely embarrassed, and quiet. I don’t think I talked to her the rest of the trip, and she broke up with me, via handwritten note, at school one day shortly after we’d arrived back home, in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

But on the bus, my friend — he was the kid whose parents smoked cigarettes in the house and had a high school brother mired in dope-smoking accusations — slid a CD out of the plastic slip. This was back when you’d pull the cover booklet out of the jewel case and tuck it behind the disc in your Big CD Briefcase. The cover depicted black men in ski masks lurking in the foreground of a psychedelic haze crazed with skulls, the album titled Chapter 2: World Domination, by Three 6 Mafia. My buddy Porter passed me his Discman, and I put on the headphones and listened to “Hit a Muthafucka.”

Chapter 2: World Domination went Gold, selling over 500,000 copies, but it was hardly some mainstream colossus, and I like to believe my Tennessee upbringing brought us a little closer to the Triple Six action. All I knew then was that it probably wasn’t something I was supposed to be listening to.

But it was thrilling. As a young boy, I was an acolyte of the macabre. I loved scary movies, even when they scared me too much to actually finish them. Years later, as a teenage burnout who could recite rhymes from The End and Chapter 2 and When the Smoke Clears and Da Unbreakables from memory, Mystic Stylez scared the shit out of me — its hood-horror-grime cover art and lo-fi beats and devil lyrics.

It’d take me a long time to listen to it front-to-back, a trepidation tantamount to the thrill of ghastliness that still beckons me towards horror. Being afraid, and enduring the macabre, makes me feel alive and human. Makes me feel brave enough to protect and care for my loved ones, to go to work, to write fiction, to kiss my girl goodnight and know the boogeyman’s not coming. The lurid artistry of grim darkness and Halloween masks and human blood thickens my skin, turns it into chrome.

Jordan Houston, who grew up in North Memphis in the 1980s and ‘90s, likewise engaged with the transcendental power of horror.

In high school, I lived in a town just outside Chattanooga, Tennessee, kind of on the edge of the country. Off-road trails and lakes and woods nearby, I rolled around in my buddy CF’s black Pontiac Firebird with subs bumping in the back, smoking dank and snorting coke before first period. It’s an Appalachian foothills community of subdivisions, trailer courts, fast food restaurants and a giant high school that looks like a penitentiary. The town’s grown quite a bit since then, an explosion of McMansions. I wonder how that’s going.

My parents’ relationship wasn’t doing so hot — money was getting bad — and I went to this ugly public high school filled with rich kids, middle-class kids, kids who lived in trailers, blacks, whites, hispanics, potheads and geeks and punks and drug dealers. I rode around with my other buddy Mike in his maroon Honda coupe with blacked-out windows selling dank, mids and schwag (whatever kind of weed was around to sell) and popping Xanax bars and selling those too. Or I’d hang with my best bud CF in the black Pontiac blaring Three 6 and Kid Rock and not selling anything, just using. It was that fucking weird post-9/11, pre-Obama era in which American Grime had seeped into suburban red state culture. Something rotten between the past and the present that you can’t put a name to. Ripped Abercrombie & Fitch jeans and subwoofers and vandalism and the school’s best-looking girls rolling into homeroom hungover as hell. I don’t know how to describe it. Is that my job here? Guess you had to’ve been there.

I was very depressed back then, and I can see that now. My on-again-off-again sweetheart at the time might still be in prison, last time I checked. My buddy Mike with the blacked-out Civic is dead of a heroin overdose, and a number of other kids I hung out and did drugs with are dead.

Mike stayed over at my house sometimes and Mom joked about his slicked-back black hair, called it a pompadour. I’d never heard the word pompadour before, and I still think it’s a funny word.

It was a lot of riding around and getting fucked up and getting into casual scrapes with the damned. Parking and partying. Buying drugs. Lusting. There were a lot of fights. In back of the local grocery store, a bunch of 15-18 year-olds would crowd up to watch a couple enraged white kids beat each other because of some ludicrous beef, usually involving a girl. My buddy Mike, the one with the Honda who’s dead, had a drug beef with this lanky, pimpled dude with a Beatles bowl-cut, and I rode with Mike to their big fight, back in an empty cul-de-sac. Mike was fucked up on Xanax and weed (and driving), and Mike burst out the car hollering shit like, “You bitch-ass pussy-ass motherfucker, come get some, bitch, you wanna fuck with me?” but Mike got his ass kicked because he was too zonked on pills to throw a good punch.

One time, I almost got in a fight myself, against my friend Matt R., because Matt R. had a large, curved nose and I drew a picture of him as a bird (it was actually a pretty decent picture) and put it in his mailbox, which really pissed off his parents, and I’d started calling him “The Bird,” and then he’d had enough. The Bird and I met up in front of a frankly disappointing crowd — a predictable turnout for me, whose personality oscillated sharply between extreme shyness and explosive bouts of jokesterdom — and we both wound up chickening out.

As our suburb started expanding into the country, there were many subdivisions in development, so there’d be a lot of fights in cul-de-sacs encircled by frame houses, empty and skeletal, and this was also a great place to hang out and take drugs. A lot of this occurred during hours in which we should’ve been at school. But the most memorable shenanigans happened at night.

Problem is, a lot of it’s hard to remember. It’s all hard to remember. Parties in spec homes throbbing, Yin Yang Twins and Lil’ John and T.I. and white kids ripping rails of blow cut with too much Arm & Hammer, wanna-be Fred Dursts donning fake diamond earrings courting dolled-up chicks in low-rise jeans, and my ass leaping out a window when the cops busted in, scurrying away into the woods, crouching alone in the dark.

Nightly gatherings in the Hobby Lobby parking lot where we’d buy pills — Klonopins, Percocets, Oxys, and lots of Xanax — and kids showing off their fake rims and spinners and subwoofers roaring and Westbrook popping his hatch, a trunk stacked with rolls of Skoal and Copenhagen and packs of Camel and Parliament cigs, like a portable convenience store for minors, because we all used tobacco, needed nicotine. Our favorite smokes were Parliaments, ‘cause we could key bumps of coke from their recessed filters. Under the media gauze of a unified post-9/11 patriotism, I think all us kids had been morphed into unwilling nihilists.

But me and CF, we’d ride on into my driveway after midnight and sit in the car and chief on a blunt and play Three 6 Mafia, very loud. I’d sink in the bucketseat and drift. I’d download MP3s of their shit and screw and chop Triple Six songs through Windows Media Player so I could hear Project Pat’s “Out There” slowed down to a low pitch that matched my high, while CF and I sat silent in … whichever car he was driving.

He had the Firebird, then throughout high school he purchased a lifted Jeep Grand Cherokee, A ‘77 Smoky and the Bandit Trans-am with the firebird hood decal, a Ford Expedition, a Chevy Chevelle, a 2001 white Pontiac Trans-am with the fluted Ram-Air hood, and I think an Escalade by the time I was nineteen or so but I can’t remember because at that time in my life I’d developed a serious diet of cocaine, Oxys, Xanax, wake’n’bake weed and tons of alcohol, whatever my ass could get my hands on. CF’s parents weren’t rich. My Tennessee buddies and I still don’t know how he bought all those cars. CF talked a lot about murder.

Anyway, in high school we listened to Three 6 Mafia while we rode around getting high and pretending to be excited about being alive.

Us suburban white kids, we didn’t know a goddamned thing about the kind of shit Jordan Houston grew up around, yet Jordan’s heavy, surreal beats and deep bass and lyrics — documenting a kind of cheerful, unbridled drug abuse and comically over-the-top violence — lent a veiled sheen of romantic thuggery upon our unrealized malaise and incredible rage. I’d sit in the car in the dark and CF got quiet, smoking a bowl of purplish dank, bathed in the blue-green light of the dash and Pioneer stereo, Three 6 conjuring images of purple neon smoke and sunglasses at night, escapism into nocturnal danger. Blue Velvet before I’d watched Blue Velvet. It was music, then, as it often is, that kept many of us from going truly berserk.

The white music we’d gotten into at the time — late ‘90s and early aughts hard rock and nu-metal — was an affair wrought purely by anger, charmless down-tuned riffs and gruff male wailing bereft of whimsy and actual swagger. Three 6 Mafia summoned complex sonic textures, exuberance and humor. This might be the real turning point by which hip-hop artistry superseded rock’n’roll. Hip-hop was closer to the spirit of Elvis Presley than anything by Creed or Godsmack or Chevelle or Papa Roach, and early aughts NYC sleaze-rock and Williamsburg indie was far, far away from impacting flyover country. There were some smart kids at school rocking to the Strokes, sure, but most of us just hadn’t gotten there yet. Three 6 Mafia’s mid-career gothic crunk, still darkly textured yet sleeker and popping with a little more color, was the perfect antidote for disaffected young crackers suffering through Nickelback country.

Triple Six rapped about Tennessee. Memphis was a six-hour drive away from Chattanooga, and I doubt many of us kids had even been there, but it felt good hollering, “North Memphis! North Memphis!” out the open sunroof in cheap sunglasses cracking open a Natty Light, getting ready for danger. Plastic bags of fireworks in the backseat — Black Cats and roman candles and cherry bombs — wondering which random mailbox we’d try and explode next. Hungry to commit crimes.

As recounted in his memoir, Chronicles of the Juice Man, Jordan Houston, after achieving mainstream success in the mid-2000s and winning an unlikely Oscar — for a song called “It’s Hard Out Here for A Pimp,” penned for the film Hustle & Flow — left LA and tried to clean up his act. Moved back to Memphis. The mainstream wasn’t for him, and he’d developed a pill problem ‘cause of quack MDs, so he moved home and got himself married, had a couple of kids, and released a solid record called Stay Trippy, and a hit song, “Bandz A Make Her Dance,” which is, it must be acknowledged, a song about flicking rubber bands at strippers.

Half of Three 6 Mafia’s original lineup would soon die. In 2013, the year Stay Trippy came out, Ricky Dunigan AKA Lord Infamous AKA The Scarecrow died of a drug-induced heart attack in his sleep, at his mother’s home in Memphis, at forty years-old. Koopsta Knicca, who’d gotten kicked out of the group circa ‘98, died of a stroke in ‘15, also at forty. Koopsta, according to the Juice Man, was a violent criminal menace, for whom The Juice holds no love, even after his death. I can only imagine that Koop, one of Triple Six’s most demonic lyricists, lived out the Triple Six ethos just a little too hard. Lola Mitchell AKA Gangsta Boo AKA The Devil’s Daughter, who rapped “I blaze the blunt up in the air just to relax and get high, the moon is full and all I see is 666 in the sky,” left the group after the success of When the Smoke Clears, citing a need to reconnect with her Christian roots, saying, “I’m not cursing in my music no more.” In 2023, at forty-three years old, Lola died of an accidental overdose. Her body possessed traces of alcohol, cocaine and fentanyl.

I OFTEN WONDER HOW MANY OF MY OLD FRIENDS ARE DEAD, that I just haven’t heard about. I’ve just turned thirty-seven. I’ve lived in different places, mostly Montana, since I was twenty-five. I visited home last fall with my girl (who always gets sea turtles with four legs) and my buddy Blake told me about another. OD’d.

“———’s dead? No fucking shit? Really? God, that’s awful.” What else can you say?

One time, Honda Mike called me up just after he’d gotten out of prison. This was maybe a decade ago. I’d already moved to Montana and got my fiction MFA and fancied myself some sprouting literary stud and I’d promised to get in touch with him again soon, but I never did. I don’t remember telling him I’d decided to be a writer. I’d just told him I’d moved to Montana. “Montana!” he shouted. This was a pretty common response. “Montana! Hell you doing in Montana?!” He sounded pretty good. He’d picked up a thicker accent in prison, and he told me, real slow and almost sensually, that he was done with heroin. That I was one of the first people he’d called when he got out, even though we hadn’t talked in years.

I’d heard thereafter that Mike had thrown himself heavily into dance, and would dress up in silky suits, and I even saw a picture of him on Facebook, when I’d still had Facebook, and he was sharply dressed and very bulky, very much a gym man, with his shirt half-unbuttoned and his chest all slick and sculpted, smiling with the other Dancers With the Stars, because Mike had participated in Chattanooga’s local iteration of television’s popular Dancing With the Stars program, just a local contest, and he had won. He was smiling and grouped up with some other very fit dudes, white, Hispanic, and black, some wearing eyeliner, all very happy. That’s the last thing I knew about Mike.

Incredible piece. Loved it.