Criminal Forms

Three kinds of thrillers — books that pull you back in — the Southern Gothic advantage — and a look back at reading and writing in 2025.

Thanks for tuning in to Pedal Steel. This piece discusses three tiers of work in the noir fiction genre-family, all of which have held an increasing influence over my own writing and literary principles or what-have-you. I also take some time to look back over this past year in reading and writing, and a near-year of using this increasingly popular newsletter software. Thanks to everyone who’s subscribed and followed and shared my work thus far and I hope I’m returning the favor in some small way. Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays and Happy New Year and I’ll see you on the other side.

This year, I read at least two mystery-thriller novels in a whole other category from your typical tight, nitty-gritty noir. They are ambitious and complex and richly written, extremely competent at the line-level—more of a “General Good Writer” voice than that which gives you the old uncanny shock and delight, wrought by those rare practitioners who keep you coming back to their books, time and again, across your lifetime. The two that come to mind are James A. McLaughlin’s Bearskin (2018) and Tana French’s bestseller In the Woods (2007). Late to the game, enjoyed both.

Bearskin is an Appalachian tale of an ex-narco-turned-Forest Service ranger (or something like that) who’s changed his name and taken exile, overseeing a Virginia wildlife refuge, steering far clear of the cartel members he’d double-crossed back in a Southwestern past life.

He begins to investigate a local redneck gang poaching black bears (for their black market-friendly gall bladders). Lovely, place-rooted atmosphere and violence and bad weather and psychedelic freak-outs and eerie anthropomorphic transformations ensue.

In the Woods is like a more understated season of True Detective—Season Three if it were set in Ireland. It takes place in a rural community south of Dublin, called Knocknaree (terrific name), in which a young girl is found murdered and left on a historic altar stone in the local wood. One of the investigators from the Dublin murder squad was a victim there twenty years prior—a child the same age as the girl. He was found gripping a tree, blood filling his shoes, the close friends he’d been with gone missing without a trace. It’s a psychological thriller told in the first person, a densely packed (smaller typeface) 420 pages.

Why I mention the page-count and typeface is just because it differs from your standard, quick-read thriller format, and both books are markedly more ambitious—with slower narrative build-ups and an elegance in their telling. And, again, highly competent at the line-level. Even lyrical, sometimes lovely. McLaughlin’s descriptions of nature can be quite beautiful.

I’ve noticed three distinct types of thriller over the years, and one is this sort of ambitious mystery (I know I’m just going to wind up using “mystery” and “thriller” and “crime” and “noir” and “detective fiction” interchangeably), breaking away from formal genre norms. Big and bold and elegant.

Sometimes such a novel triggers buzz, cross-genre appeal. Even awards. But I also mentioned that these novels don’t necessarily possess moments or bursts of prose that call you back for more and more and more, well after you’ve finished the book. You might re-read it, but you wouldn’t tell a literary friend: “Jesus, check out this paragraph on page ninety-one.”

I liked these books very much and am going to get another Tana French novel as soon as I’m able. But the wonky, surprising sentences found more often in literary fiction aren’t really a significant part of the package. There’s some secret ingredient, unnamable, in a Denis Johnson work that just doesn’t appear in lots of even highly acclaimed detective fiction.

This isn’t a knock. Functionally, it’s just not that necessary for the genre. Think of a book that’s pure lyricism—like Barry Hannah’s Ray, or a recent Booker Prize-winner, Samantha Harvey’s Orbital. These would not be very compelling stories without that poetic backbone. The cinematic narratives of ambitious mystery and thriller novels are the chief aims for their authors. Any striking, poetic prose here is just a bonus, and too much of that would get in the way of the story.

Then there’s your second kind, your standard hardboiled noir that clocks in under 325 pages and the prose is no-nonsense, even if it exudes a little atmosphere and panache. Two Scandinavian (“Scandi Noir”) authors I like are Henning Mankell (Faceless Killers is terrific) and Ragnar Jónasson (the Detective Ari Thor mysteries are good). The Scandi Noir genre is great because you have that baked-in, frigid atmosphere. But they’re very straightforward as far as style. Page-turners. Icy and clean. When this mode is done well, very good stuff.

Two novels I read this year, James Lee Burke’s The Neon Rain (I’m embarrassed this is the first time I’ve read it) and Peter Farris’ The Devil Himself, are of a third kind.

This kind of novel can be twisty or complex or ice-cold and straight as a plumb line, whatever, but there’s something in the prose you have to get back to.

James Lee Burke was greatly influenced by Faulkner as a young man, wrote more literary work early on, and his 1986 novel The Lost Get-Back Boogie was published by a small press (Louisiana State University) and nominated for a Pulitzer. It was in 1987 when Henry Holt published his hard boiled detective novel The Neon Rain, the first of the Detective Dave Robicheaux series.

It’s obviously tied to genre conventions in a profound way, has commercial appeal, all of that, but Burke is a uniquely gifted writer. His story is that of a struggling young writer with literary ambitions who broke out, able then to support his family with writing, by dropping through the trapdoor of commercial and genre fiction. You can’t fault the hustle, and his virtuoso chops bleed into the pages of his noirs. He’s funny as hell too, and the so-sticky-and-close-you-can-feel-it-under-your-fingernails sense of place in his work has a depth that can only be achieved by a master.

The writing itself has a personality, plain and simple, one you’d like to get another beer with as soon as you’re able. You’d like to be best friends. There are flashbacks to Robicheaux’s time in Vietnam that are so vibrant and hallucinatory that Burke’s ambitions as a stylist—in addition to being a storyteller—rise up, making you do a double-take. There’s a surreal scene in which the detective’s on a bender and runs into a band of ludicrous carnival folk in a bar that feels wrought by Denis Johnson (Bringing him up again. Johnson was not a stranger to the detective fiction mode), or even Cormac McCarthy.

Farris’s The Devil Himself (2022) is a pitch-dark Georgia noir about a victim of sex trafficking breaking loose from her captors in a field of scarecrows, then taken under the wing of a violent old man married to a mannequin. Its prose is reduced to a cast-iron-dark demi and he takes risks with humor and grotesqueries that veer from Tarantino-esque violence and into the absurd. He pulls it off because he’s such a confident writer, and there’s a darkness he allows into his fiction that many noir novels only claim to possess. He’s a master of metaphor, too, and there’s a distinct poetic undercurrent beneath Farris’s largely plainspoken delivery. I’ve read the book—and then I’ve read the book again, this writer going back to take another gander and see how it’s done.

As far as I know, most of Farris’s books are first published in France, to considerable acclaim, and then occasionally picked up by presses in the US. The Devil Himself was released by Arcade Publishing’s noir imprint Arcade Crimewise, several years after it’d been published in France. However, I’ve yet to get a hold of a few of his books because they’ve never found an American publisher. Which is absolutely wild to me considering his talent. Look at his website. It’s like half the website’s written in French. But, you know, for me this only adds to guy’s mystique.

Anyway, what am I getting at? Okay. I’d recommend any of the above-mentioned authors and books. I tolerate, in genre fiction (chiefly thriller/noir and to a lesser degree horror), the straightforward and conventional, the competent, the highly competent, and then what’s masterful or delightfully strange.

I don’t give the same leeway to literary fiction, and not because it’s more aspirational.

I don’t really care if it’s aspirational. If it’s sublime, it’s sublime and you just know it. The good stuff is very, very good. But even a mediocre work of literary fiction can be very, very bad. It’s not because the lit fic book failed to live up to it’s ambition (and it surely did, if there was any ambition to begin with). It’s because it won’t be worth your time. There’s nothing to offer a reader. It’s like the acquaintance or friend-ish person who shows up to dinner or a party with no good jokes, or even a six-pack.

Genre fiction often scratches the same itch that film does. You’re far more lenient with it. Bad literary fiction can be boring, self-indulgent or navel-gazy, propagandistic or moralistic yet bereft of aesthetic soul; it can be formally gimmicky; it can read like a semi-autobiographical screed no one on earth ever asked for; it can be insufferably twee and urbane and possess no magic or stylistic rigor and just exist because the writer went to Iowa and feels an obligation. I don’t know, there are a million reasons why bad literary fiction is so much worse than an airport throwaway that keeps you guessing who the murderer is.

Peter Farris and James Lee Burke have an advantage too because their works exist in the Southern Gothic province. (Disclaimer: I am very, very biased towards this little genre whose twentieth century heyday I long for, and whose books nudged me into the pursuit of writing fiction.)

Much great Southern Gothic fiction bears genre elements and its best practitioners achieve literary gravitas with language—while also offering a blistering or shocking or bizarre story. Story, story, story!

In the twenty-first century, in fact, these books are now generally labeled something along the lines of “country noir” by default, such is their relationship with thriller, crime and horror tropes and pacing. I’m thinking of Daniel Woodrell (RIP), Michael Farris Smith, Ron Rash, and definitely Peter Farris. Lots more.

The old Southern Gothic label seems now to be used—insofar as the books are marketed—for commercial spooky family sagas set in the South. But it used to be applied to books like Cormac McCarthy’s Child of God and Outer Dark, slim tales told in lyrical yet hard-pan prose whose narratives could easily—if released today—be Horror-categorized by booksellers. Harry Crews wrote a lot of depraved fiction, and Flannery’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” is about a family meeting their fates at the hands of a serial killer. Faulkner’s Sanctuary comes to mind. William Gay’s Twilight is horror-adjacent in the vein of early McCarthy, and many of his short stories feature dead bodies.

I guess my point—if I have one—is that Southern Gothic has always been at least cross-genre-curious, even for its writers with the highest of literary aspirations. It is borne of a violent, nasty region to which its artists hold deep spiritual ties bordering on obsession.

Anyway, I have nothing else to say about any of the above. Talking about some books I’ve read in 2025 also just gives me a chance to look back on a good year for reading and an exciting year in writing and publishing.

Once the ink has dried, I’ll be making an exciting announcement regarding my forthcoming contribution to our beloved Southern Grotesque Letters. Stay tuned.

Speaking of Southern Grotesque Letters, one of the best novels I read this year was Lee Clay Johnson’s Bloodline, released by County Highway’s new Panamerica Books, which I covered here. Please read that, and read his fantastic noir-grotesque debut Nitro Mountain (Knopf).

Here are some other books I read for the first time this year that I enjoyed, and with some bloated assessments of what genre they actually are, avoiding the word “literary”:

Hard Rain Falling by Don Carpenter (Pacific Northwest Noir/Prison Drama, borderline Rockabilly Noir)

The Killer Inside Me by Jim Thompson (Hard Boiled-ass Psycho Noir)

The Trees, Percival Everett (Horror-Satire)

Off Season by Jack Ketchum (Stone Cold Rural Cannibal Horror)

A Head Full of Ghosts by Paul Tremblay (Possession Horror)

SEEK by Denis Johnson (Non-fiction/Alt Reportage/Whacko Americanzo Gonzo (I just recently came up with this stupid fucking genre name))

Lee Johnson’s Bloodline is also “Whacko Americanzo Gonzo”

Faulkner’s Sanctuary (Mildly Impressionistic Country Noir)

The Darkness by Ragnar Jónasson (Icelandic “Scandi” Noir)

When the Clock Broke by John Ganz (1990s Whacko Americanzo Gonzo Political History)

Perchance to Dream by Charles Beaumont (Short stories covering the full gamut of “speculative” fiction by one of the OG “Twilight Zone” writers)

Galveston by Nic Pizzolatto (Crime/ Texas Noir) — fun times reading the first work by the man who created season one of True Detective

Night People by Barry Gifford (Rockabilly Noir (look it up))

The Revenant by Michael Punke (Histotical/Western/Survival-Adventure)

Hell House by Richard Matheson (Very 1970s Sleazy Haunted House Horror)

Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption by Stephen King (The genre is “Stephen King”)

These books, as well as Bearskin, In The Woods, The Neon Rain, and The Devil Himself, represent the kind of mix I’ve been looking for, further diversifying my literary diet. You’ll learn more techniques by reading across genres and across levels of technical or aesthetic mastership.

Faulkner told us, “Read, read, read. Read everything—trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it. Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You’ll absorb it. Then write.”

Some of my re-reads this year fit into this mix, and while revising my novel earlier this year I frequently revisited James Dickey’s Deliverance, Davis Grubb’s Night of the Hunter and Cormac’s early Tennessee novels. All books I’ll go back to time and again till I’m dead.

And now I look back on another year in reading and writing and living:

This year, I started a newsletter in February called “Puryear’s Southern Lit Jukebox” (of course) and then renamed it “Pedal Steel” in the summertime, hoping to broaden the whole vibe of the newsletter. It’s been a hell of a lot of fun running this thing, and it’s provided a significant outlet for my writing, a place where I can run a little wild and blow off some steam, and I’m grateful as hell to the two-hundred(ish)-and-counting folks who’ve decided my writing is worth hitting their inboxes every month or so. Thank you.

It started off as a place to talk about Southern fiction but rapidly morphed into a venue for unhinged American noir essays, of which I wrote a kind of triptych: Rockabilly Noir, His Master’s Voice Is Calling Me, and Slasherland. I won’t be able to write any essays like that again, not for a while. You shouldn’t expect much of that from a newsletter. It’s a testament to the craft that you just can’t bang that shit out.

This software gathers a lot of writers, from all stages of their careers, writers with different goals, established and unknowns and self-published and traditionally published authors. A very vocal anti-establishment cadre exists here—which is necessary in any literary era—and many of these folks read a popular lit crit journal called The Republic of Letters. I wrote a piece for that journal defending MFA programs, which was kind of the first thing I wrote this year that was noticed by more than twenty people. Seemed suicidal, given how aware I was of the vibe. But you gotta arrive swinging, and honest. Some people actually liked it.

Some of the best culture writing I’ve encountered this year has appeared on this platform, by independent writers. Right now, it’s filling some gaps as traditional media outlets purge their book reviews sections and magazines like Esquire are publishing recaps of Stranger Things episodes and not much else … and I guess don’t publish fiction anymore?

Sometimes I get a little tired of reading takes on how shitty and middlebrow everything is now, and wish many of these independent authors would spend less time writing polemics and more time creating genuinely strange and unique art and seeking out contemporary stuff that fits the bill (it does exist, you just have to look harder). One of my favorite newsletters on here is “Counter Craft” by Lincoln Michel because he offers more clear-eyed takes on the books and publishing landscape. Naomi Kanakia’s “Woman of Letters” offers a similar reprieve, and these writers have experiences in both traditional and indie realms, which uniquely positions them to report on literary matters through a sober lens.

Altogether, being on the platform has enrichened my own literary diet, adding a whole other, much-needed layer in 2025.

In April or I think May, I signed with a literary agent, still a shock to me. I’d started seeking agents about five years ago. 2025 was starting to feel like a very writerly year for guy who was starting to really feel the ravages of rejection and doubt. About fifteen years in the trenches.

In June, my first child was born. In the fall, we took an amazing road trip back down to Tennessee (I live in Montana), and all over the country, and it was around that time when things started looking good for my book. I managed to place a couple stories in journals, met some cool people and made some meaningful connections, and continued working again with Zach Dundas for the American travel and culture publisher and magazine Wildsam. There isn’t a single writerly milestone or thing I’ve written this year that doesn’t feel true and consequential and I’m more grateful in 2025 than I’ve ever been. Surely 2026 is going to be a disaster.

This will be my last post until the new year. It’s winter. Time to hunker down and get some writing (fiction) done. I don’t have anything to say, or any clever way to end this thing. Nothing brilliant on my mind. Like I said earlier, you shouldn’t expect too much, not all the time, from a newsletter, whose model is “post enough so you don’t lose subscribers.” And great writing takes time. It comes. It goes. It takes on new forms.

Life goes into new forms - Neal Cassady

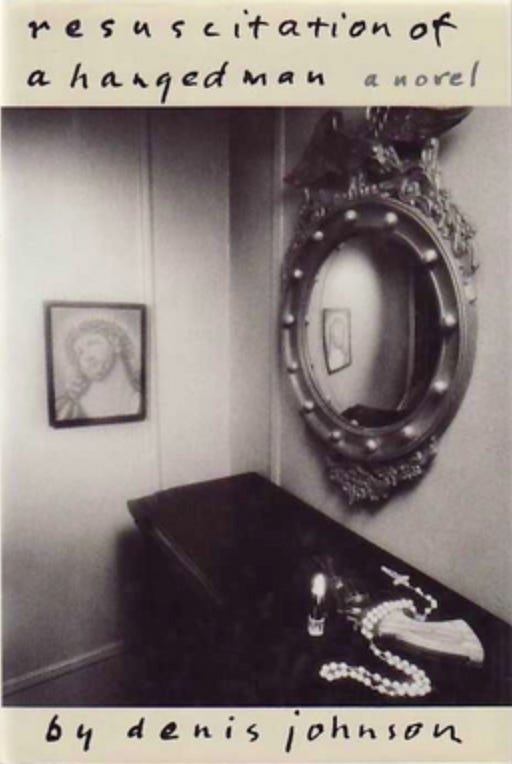

This is the epigraph that opens Denis Johnson’s novel Resuscitation of a Hanged Man, a story about a suicidal Cape Cod-transplant who gets work as a disc jockey, yet starts doing a little private detective dabbling on the side. I think Johnson knew the detective novel was a kind of trap door into more propulsive narrative zones—and perhaps sales; evidently Johnson was still using advances and rights acquisitions to pay off considerable debts, well into his life of literary repute. (Although I doubt Resuscitation yielded much sales; it’s just as unwieldy as a handful of other out-of-left-field Johnson pursuits; it’s also fabulous, by the way.)

But Johnson was a chameleon, who likely followed Faulkner’s advice. He started out as a poet, was a junkie and a liar and a criminal. He wrote novels. He wrote American Gothic road novels (Angels), post-apocalyptic novels (Fiskadoro) and got sober. Moved to the Idaho woods. Probably relapsed somewhere along the line. Moved to the California coast. Married three times. Wrote a strange, gorgeous Western (Train Dreams) and then a straight-up Heist novel (Nobody Move).

Who the hell knows what else he did. You change. You’re good and then you’re bad and then you’re good again. Then you’re bad again. You write at all levels. You keep going. You have no idea what’s going to happen to you. You have no idea what your life and who you are is going to do to other people. How and what you’re going to write. Life goes into new forms.

Tremendous article Brett. Yep James A. McLaughlin’s Bearskin (2018) was a mammoth read. Am yet to read Panther Gap (2023).

Very happy to have found your substack and am looking forward to your future essays! Also please keep feeding us those book recs. I always feel an extra groove being etched in my brain after reading one of them.